More and more, I’m aware of feeling like I need to justify loving imperfect books. Especially when the imperfections are slight and structural and the consequence of having been made by humans, and the reason that I love the book (or story) in question is because it normalises queerness in multiple directions, or decentres classic Western visions of fantasy and science fiction in favour of exploring other ways of being in the world. Or both at once. It makes me feel exposed in ways I’d rather avoid.

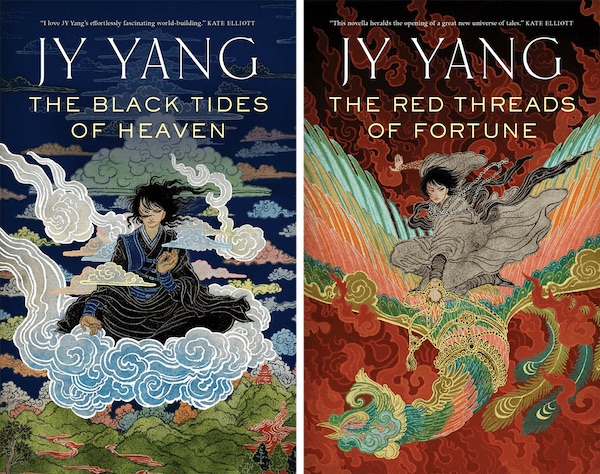

The Black Tides of Heaven and The Red Threads of Fortune, the first two novellas in J.Y. Yang’s Tensorate universe, on the other hand, don’t need me to justify anything. They’re very different stories, and each is excellent in its own way.

One story—The Black Tides of Heaven—takes place over the course of thirty-odd years. It’s a coming-of-age story, a story about growing up, and growing out, and growing into one’s self and one’s relationships. The other—The Red Threads of Fortune—takes place over the course of only a few days. It is a story about coming to terms with grief, about learning to live with loss, and to find happiness again. It’s also a story about trust, betrayal, and family. Though, to be fair, both novellas are stories about family.

The main characters in both novellas are the twins Mokoya and Akeha. They were given to the Great Monastery as children by their mother, in return for a favour by its abbot. Their mother is the Protector, a powerful and repressive ruler, and despite their monastery upbringing, neither Mokoya nor Akeha can escape her influence on their lives. Mokoya develops a gift for prophecy, which the Protector makes use of to support her rule. Akeha, on the other hand, rebels as much as possible, and ends up joining the revolutionary Machinists, who oppose the Protector’s rule outright.

I don’t intend to discuss the plots of each of the novellas in detail. Black Tides is Akeha’s coming-of-age, while Red Threads is Mokoya’s learning to live again after the death of her young daughter—and meeting and falling in love with the enigmatic Rider, while a giant flying naga threatens to destroy a city. Instead, I want to talk about the elements that, quite aside from the great plots and brilliant characterisation, made me fall in love with Yang’s work here.

It all comes down to worldbuilding. Delightful, amazing worldbuilding. This is a world in which magic—the Slack, which trained people can use to manipulate the elements—co-exists with technological development. Increasing technological development in the hands of the Machinists has lead to conflict, because the magicians—”Tensors”—understand that their monopoly on doing certain things will be challenged by these developments. And since the Protector relies on the Tensors, Machinist development is inherently just a little bit revolutionary.

This is a deep world, and one that has had a significant amount of thought put into it. It’s also full of cool shit: riding lizards, giant flying beasts, monasteries that have interestingly complicated histories and relationships to power, explosions, revolution. (And mad science.)

And it’s… I don’t even know if I have words to talk about what this means to me, but this is a world in which children are they until they decide they are a woman or a man. But Yang also writes space in there for people who don’t want to choose, who don’t feel that either fits. This is a world where gender is a choice, and one where the choice still imposes constraints—but it feels freeing, to see in these novellas another approach to how people and societies could treat gender.

It’s also really delightful to me that all the relationships that the novellas actually show us are queer relationships, or polyamorous ones. Or both. The default here is not straight, and it’s a breath of fresh air for your queerly bisexual correspondent.

Yang’s characters are really interesting people. And people that it is easy to feel for, even when they aren’t making the best possible decisions. They are intensely human, and complicated, and Mokoya and Akeha’s sibling relationship is both deep and, as adults, fraught, because they’re different people with different approaches to life.

I really love these novellas. I can’t wait to read more of Yang’s work. When are the next instalments coming? It can’t be too soon.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.